Spectators can try most sports for themselves, but Formula One motor racing is different. Only a top-level racer can appreciate the sensory violence inflicted by a single-seater F1 car on its driver. Even the on-board cameras that have thrilled TV audiences in recent years only tell half the story. But last summer I headed to Donington Park, one of Britain’s best racing circuits, for a ride in one of Minardi’s two-seater Formula One cars. Never mind that the low-budget Minardi team usually languishes at the back of a Grand Prix grid – the two-seater that it calls the F1x2 is still an explosive, 800bhp projectile which promises to batter my senses and redefine my perceptions.

“You think about the amount of people that have been involved over the years in Formula 1 either as fans, sponsors, enthusiasts, whatever, and they very rarely ever get to feel or touch a car,” says the Minardi F1 team’s Australian boss Paul Stoddart, “but the thought of riding in one just didn’t exist.” Until the two-seater came along. “We started running it in 2000. By the time we complete this weekend here we’ll have put 700 very, very lucky people through this programme, all around the world,” he adds. Today, at the Minardi F1 team’s Thunder in the Park event, I’m going to become one of them.

At Donington I tried to find out what I’d let myself in for. Who better to ask than Damon Hill, 1996 Formula One World Champion, there to give rides to a lucky few and in the process raise money for the Brain and Spine Foundation and the Down’s Syndrome Association. These days Damon runs P1 International, a club offering members the chance to drive a pool of exotic road cars. Does driving a Porsche or Ferrari on the road compare with an F1 car on the track?

Damon shook his head. “It’s a factor of 50 greater than anything a road car can do. The biggest difference with a Formula One car is that it has aerodynamics, so the faster it goes the more it sticks. That’s completely the reverse to a road car.” The Minardi, in common with single-seater Formula One cars, has upside-down wings front and rear to provide ‘downforce’ – along with careful detailing of the whole car’s shape to help maximise its grip without causing excessive drag. “What your mind tells you is that the faster you go the more likely you are to slide. In actual fact to some degree the opposite applies. Obviously there’s a limit…” His voice, reminiscent of his double World Champion father Graham’s, trailed off into a laugh that lit up those trademark piercing eyes.

“The first half lap you’re going to have to do a lot of readjusting, because things are a lot faster than you’ve probably ever experienced before,” warned Hill. “But then the next thing you’ll feel is the grip that you’ve got, and you’ll start to feel reassured by the fact that it seems to stick when it appears that it wants to fly off the road. And the next thing you’ll find is that you can’t believe how late it can brake.”

According to Stoddart, who regularly drives the Minardi two-seaters himself, passengers often try to brake for themselves: “They see the 300 metre board, they see the 200 metre board, they see the 100 metre board, you’re still flat out, 200mph in sixth gear, and then they see the 50 metre board, and because their feet are right next to you can actually see them trying to brake. That’s an amazing experience,” he chuckles. “In the dry you don’t touch the brakes until the 50 metre board and it goes from 200mph down to 60mph in 40 metres, basically, and you’re down four gears as well. That brings it home to people.”

How close is that to the ‘real thing’ – a single-seat Formula One car? Also present at Donington was Alex Yoong, at the time a Minardi Grand Prix driver but shortly to be replaced after a string of disappointing races. Yoong reckoned the sensations are incredibly close. “From the passenger’s point of view it is very much like the Formula One car,” said the Malaysian. “From the driver’s point of view we drive day in day out Formula One cars, so these cars will feel slower to us, and a bit heavier and a bit more bulky.”

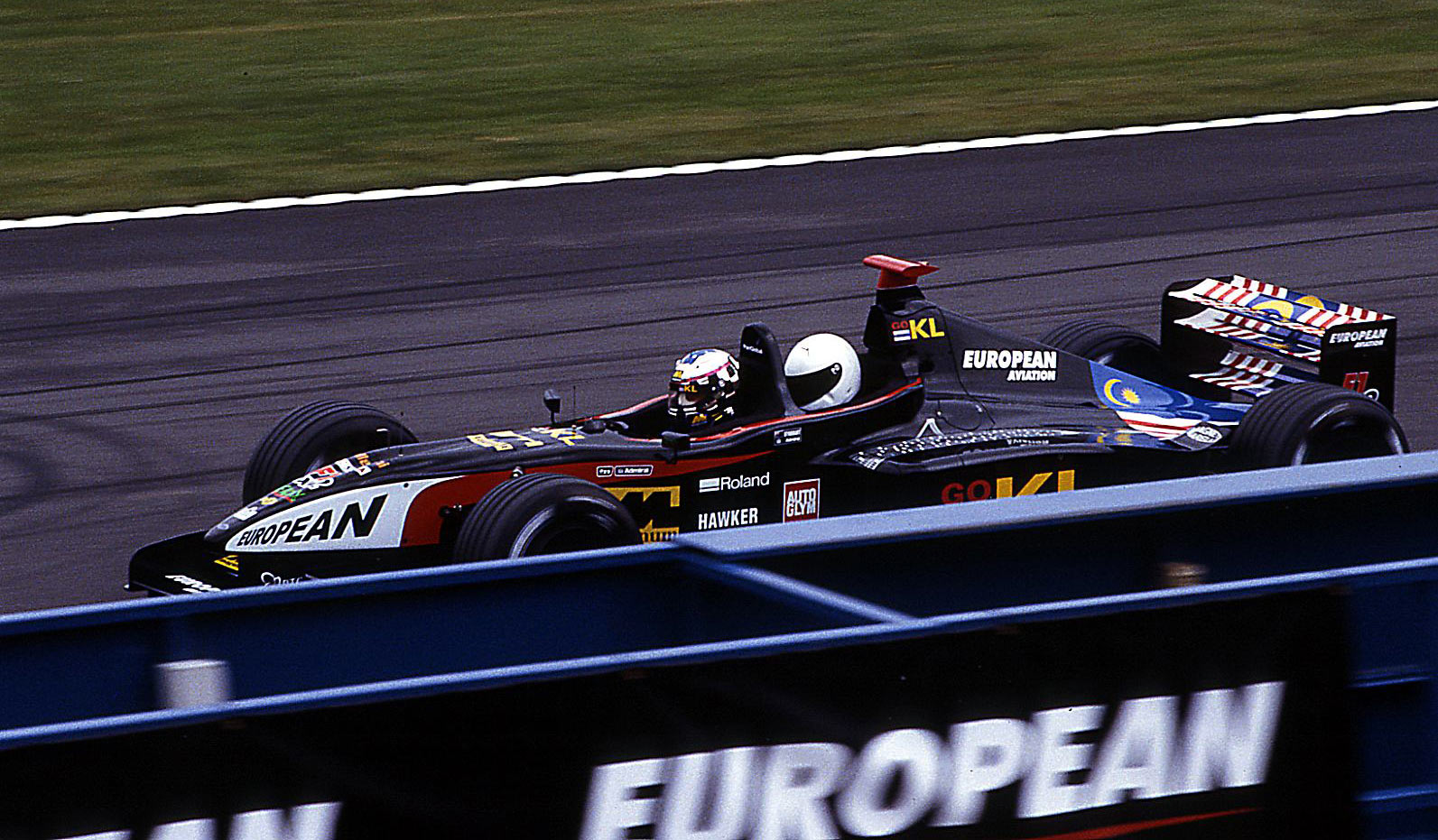

Alex Yoong at Donington: 'From the passenger's point of view it is very much like the F1 car’

“We’ve had them out against each other,” revealed Paul Stoddart. “In simple terms, on a 1m20s lap we’d be four seconds off. You’re trading off weight.” But, interestingly, the slightly longer two-seater is in some circumstances even quicker than the F1 car. “Mid-corner it’s a little bit more stable,” explains Stoddart, “but most certainly it comes out much cleaner and quicker, as indeed does any longer wheelbase - it’s not rocket science.”

So, there I was about to be strapped into the back of an 800bhp racing car which could lap within a few seconds of a full-blown F1 racer – and catapult out of the Donington corners even faster. Can anything compare with that? Alex Yoong thought carefully. “Competitive water skiing is pretty serious. When you’re slaloming and jumping you’re generating a serious amount of speed. Otherwise, no. I think driving Formula 1 is pretty much enough!”

Since his retirement from Formula 1 had Damon Hill done anything which gave him the same kind of thrill as driving a Formula One car? “No, I’ve had my fill of that,” he laughed. All weekend journalists would be asking the 41-year-old whether this Minardi drive signalled a comeback to F1, but Hill has stayed away. He hasn’t lost his love of speed, though. “Once you’ve got that in your veins I’m afraid you’ll never get rid of it,” he said. “You’re always going to be looking occasionally for a bit of a thrill. But I can do it with some friends karting or something. I still like motorbikes, I ride off road. But I’m not mindless about what I do, I don’t want to go bungee jumping or anything like that.”

When I asked Paul Stoddart if he has found anything to compare with driving an F1 car, I was taken by surprise when he said yes. “My other passion/business is aviation and over the years we’ve owned a lot of different types including a MIG fighter. I had a bit of a fly of that and it was a seriously interesting experience. We put a few passengers up in it, not many, and a lot of them didn’t feel terribly good when they came down,” he recalls - adding that at least the Minardi two-seater passengers usually come back ‘in one piece’…

You have to prove you can cope with it first. Multi-page medical forms include details of height, weight and waist size, because anyone expansive of girth or long of limb simply won’t fit into the Minardi’s back seat. In size, at least, I’m thankful for my averageness. I have to declare any medical conditions, and provide details of next-of-kin: a salutary reminder that even with all the precautions, this is still a dangerous sport. Then it’s off to the doctor, who pronounces me ready for action after a quick check-up.

Now I have to don fireproof underwear and the heavy, multi-layer fire-resistant race suit, then select gloves, boots, balaclava and helmet. It’s starting to sink in that I’m really going to do this. Damon Hill’s words from earlier in the day force their way back into my head: “You’re going to feel nervous, if you’ve got any sense,” he had said. But there’s no time for nerves now.

As I arrive back in the pits, rain starts in earnest and the order goes out to change the cars over from dry-weather tyres – with their regulation four grooves – to fully-treaded ‘wets’. Mark Webber, then Minardi’s other F1 driver who has since hit the big time with the Jaguar team, looked ruefully at the rain. “It’s OK in the wet, but you just don’t get the same experience,” he explained, adding that the two seaters were around 15 seconds a lap slower in those conditions.

Damon Hill gets ready to take the Minardi F1x2 two-seater out

... meanwhile Mark Webber waits in the sister car

‘My’ driver, Minardi tester Matteo Bobbi, already has his balaclava and helmet on, and it’s time for me to do the same, remembering to insert the essential earplugs first. The frenetic scene before me is suddenly silent and calm. Voices seem distant, mechanics wheel trolleys loaded with tyres and equipment noiselessly past. All I can hear is my heartbeat. It’s my turn.

You step into the cockpit, then hold yourself up on the sides and wriggle your legs into the car, as you’ve seen so many racers do. A mechanic reaches in to connect up the six-point safety belts, leaning so hard on the shoulder straps that you’re compressed into the car. The neck protector around the cockpit edge goes on, the mechanics take a step backwards – and you’re moving.

As the Minardi is rolled silently out of the garage you lower your helmet visor, then remember to open it again just a few millimetres – the airflow will prevent it misting up. There are distant shouts, a jolt from behind. Silence.

Shattering the calm, the 3.5-litre engine just inches behind you explodes into life. This is thunder in the park, all right. The whole car judders as Matteo selects first gear, the engine screams, and you’re rolling down the pitlane.

Second gear, third already. Matteo whips those 800 horses into a frenzy of wheelspin for the short sprint to the first corner, Redgate, a long right-hander which leads into the spectacular Craner Curves. Water streams off the front Michelins, big in your view, as you accelerate down the hill, the engine blaring behind your head and your body tensed against the g-forces as the car sweeps right. In an instant the Minardi slingshots left, and the savage change of direction catching you off balance.

Before you know it the Minardi arrives at Old Hairpin, really a fast 90-degree right-hander where Matteo has to fight the car into the corner. It catapults out, flashes under Starkey’s bridge to the tight hill-top right-hander at McLeans, where for the first time Matteo really works the brakes hard, throwing you against the harness. You grip tightly onto the safety button: let go and it flashes a warning to the driver that something’s wrong, but you don’t want to let go. Barely does the braking force subside than the Minardi flings you sideways in the cockpit, the staccato engine note betraying the traction control system’s efforts down the short straight to Coppice corner.

The cornering forces build through this long right-hander as Matteo feeds in the power, then grabs fourth, fifth, sixth gears along Starkey’s Straight. There’s barely time to register the bridge over the circuit and the pits coming up in front before Matteo is on the brakes again, the Minardi biting into the tarmac despite the rain.

Hard left, hard right through the Esses and then down to the Melbourne hairpin behind the pits. It seems so slow, but as the Minardi starts to straighten up Matteo is back on the throttle, fighting the car as the rear wheels spin and slide sideways, punching up through the gearbox along the short straight then hard on the brakes again for the left turn at Goddards. You’re over the line, a lap on the board already.

Pit garages race by, and the 160mph slipstream tries to suck the crash helmet clean off your head as the Minardi races downhill to Redgate. Now you know what to expect. The long Redgate corner takes an age, then you brace yourself against the g-forces through the Craner Curves and that snap direction change at the bottom of the hill. Matteo is pushing harder now, exploring the limits as the tyres and brakes get up to their optimum temperatures. You gasp for air as he hits the brakes at McLeans, lean your head to counteract the g-force the Minardi is pulling through Coppice.

The 15,000rpm howl of the engine fills your helmet and rain streams off your visor as you race down to the Esses again. Matteo crams on the brakes at 185mph. Too much. The blur of the tread pattern on the left front wheel suddenly snaps into focus, frozen before you as the wheel locks. Strapped tightly into the car, you can feel the rear wheels sliding sideways as Matteo fights to slow the Minardi for the tight left/right Esses. But it’s too late.

Everything happens at once. The brakes ease off and those huge front tyres begin to roll. Matteo turns in hard but the nose of the Minardi runs wide on the greasy surface. You’re just going too fast. There can only be one outcome. Before you know it, your vision is full of flying gravel as you bounce over the gravel trap, the grass and the rumble strips and back onto the track.

For a second, the Minardi is just rolling along and you sense that inside his multi-coloured helmet Matteo is cursing himself for this untidy display. Then he finds a gear, the motor screams, and you’re hurled towards the hairpin – where Matteo’s line is inch-perfect – and on past the pits.

Earlier in the day someone mentioned that after four laps of this, most passengers just want to stop. But you want this to go on. The speed, the g-force in the corners, that awesome ability to flick from one direction to another in the blink of an eye. It’s addictive.

Yet suddenly it’s over. Pulling out of Goddards onto the main straight, you’re ready for the scream of the engine and the shove in the back, but it doesn’t come. Instead Matteo drops down a gear and the Minardi slows gently. It peels left off the circuit as a klaxon sounds to warn any pitlane jaywalkers. You’re out of breath, sweating: it’s hard work bracing your body against the incredible forces generated in the corners and the braking areas. Yet you want to go back for more.

A few lucky passengers got more, as Thunder in the Park featured a 15-lap ‘race’ which saw all eight Minardi two-seaters on track at the same time. The first of these events in 2001 saw former World Champion Nigel Mansell on hand to drive one of the cars, giving passenger Jonathan Frost more than he bargained for when they tangled with another car (driven by Fernando Alonso, now racing in F1 for Renault) in the final corner. Frost was back the next year and had another fright when Mark Webber spun their car, leaving Formula 3000 racer Giorgio Pantano and champion boxer Chris Eubank to cross the line first. It provided an amazing spectacle for the Donington crowds, and helped the event raise more than US$500,000 for charity.

Every single passenger I met fizzed with enthusiasm for the whole experience, which Paul Stoddart confirmed was generally the case. “I’ve had quotes like ‘it’s the best thing I’ve ever done in my life’, ‘it’s better than sex’, ‘I could die and go to heaven’, we’ve had all of that. We’ve put a lot of smiles on a lot of faces.”

Mine included.